Museum research and presentations of the corporate history of the Goedewaagen group

The Goedewaagen Ceramics Museum was founded for the scientific study and presentation of decorated Dutch industrial earthenware from 1875 to the present. This objective is partly a result of the company history of the Goedewaagen-Gouda BV ceramics factory, established in Nieuw Buinen since March 1983. Goedewaagen's company history goes back in a direct line to a large number of ceramic factories described below in their relation to the Ceramic Museum.

Through the systematic research that the museum staff has been carrying out since its foundation, together with collectors-documentarians, art historians, glaze specialists, ceramists and, last but not least, well-informed employees from the various ceramics factories themselves, the Ceramic Museum Goedewaagen aims at preserving the National Heritage that is contained in the production of the present factories.

Since 2000, the Dutch Ceramics Museum has been building up a digital collection of photographs, catalogue images and other types of documentation about the production of Dutch earthenware factories in terms of models, decors and the ceramic techniques used. This museum research resulted in the three-volume English-language handbook by R. Tasman, Gouda Pottery Book, Rotterdam (Optima Publishers) 2007. Museum curator Friggo Visser acted as chief editor for this project in which a detailed company profile of 64 large and medium-sized factories, their designers and employees was given.

In close consultation with the Goedewaagen Ceramics Museum, the production research, which has been continued in more than twelve working groups, has been the responsibility of the Willem van Norden Scientific Institute Foundation since September 2010. The museum's point of departure in this research is the collection, now numbering almost 4000 items, that has been built up since 1989. The following factories are central to the research:

Goedewaagen's Royal Dutch Pipe and Pottery Works in Gouda, originally founded as a pipe factory by P. Goedewagen in 1779. In the 19th century the factory acquired an international trade position as a pipe manufacturer and therefore had the capital to take over high-quality brass moulds from smaller Gouda pipe factories that had run into economic difficulties. In 1909 Goedewaagen moved into a for that time ultra-modern new factory at the Jaagpad in Gouda, just outside the former city wall. Aart Goedewaagen I also took the initiative for company tours as a newspaper article in the NRC of 1911 reflected. A tradition that the factory continues to this day. Since 2010, these guided tours have taken place under the responsibility of the Ceramic Museum, which also verifies the ceramic-technical and art-historical qualities of the story.

Another tradition within the firm is that the company history for the production of Gouda clay pipes was also studied from within the firm itself. Together with Dr. Helbers, the director of the Municipal Museums of Gouda, Dirk Abraham Goedewaagen published in 1942 a leading publication on the Gouda stone pipes.

The last Goedewaagen director, Aart III, gave in 1974 the executive archives of Goedewaagen to the pipe archivist Drs. Don Duco of the Pijpenkabinet, initially located in Leiden and now in Amsterdam, for a scientific study on the Royal Goedewaagen. For this task the archive was entrusted on loan for a period of 30 years to the Municipal Archives of Gouda, now the Regional Archives Hollands Midden. In 2000, Primavera publishers in Leiden published Don Duco's study. Neither the archives of the Schilderzaal and the Laboratorium present in Nieuw Buinen and managed by the Keramisch Museum, nor the collection that has since been created, were used by Duco.

For the determination of Goedewaagen pipes the Ceramic Museum refers to the Pijpenkabinet. In our own museum the pipe history is only presented in an educational way. Different is the museum research on the Goedewaagen production of decorative and functional pottery, monumental sculptures and small plaques, tiles, tile tableaux and mosaics. With the support of a large number of collectors, the Ceramic Museum has been working for about 15 years on the scientific description of sub-collections of Goedewaagen earthenware. See also the programme of the Scientific Institute Willem van Norden.

This research includes the Drenthe history of the earthenware factory Goedewaagen. In 1963 Aart Goedewaagen III bought a factory at Glaslaan in Nieuw Buinen for the production of crockery and Delft blue, which had previously been owned by the clothing factory La Vita. In the ten years that followed, pottery production was successively transferred from Gouda to Drenthe. In the meantime, several new factory halls had been built. In 1974, the factory building on the Jaagpad was sold off and demolished for housing development. Only the design department and the sales office remained in Gouda.

Shortly after the last departments were moved to Nieuw Buinen in 1982, Goedewaagen's Koninklijke Hollandse Pijpen- en Aardewerkfabrieken went bankrupt, partly due to the energy crisis of that time. Under the leadership of the former sales manager J. Kamer the factory restarted in March 1983 as Goedewaagen-Gouda BV.

The popular pottery factory and potter's shop De Star in Gouda. De Star or Starre is Gouda's oldest known pottery factory within the ramparts, of which the earliest record dates back to 14 May 1612. Its founder was Jacob Pietersz, a terracotta potter trained outside Gouda. Beyond the medieval tradition of Dutch utility pottery went Mels Maertensz. Brouckert, the 3rd owner of the property. He acquired the exclusive right to make pipe pots for the oven. Later he also obtained the monopoly on making sugar pots and funnels for the sugar refineries.

The Goedewaagen family bought this pottery and earthenware factory in 1853 so that the pipe maker, who was not allowed by Gouda law to fire pipes himself, could from then on manage as many pipe kilns as possible. Goedewaagen continued this craft until 1950. The Ceramic Museum documents how from the 1930's hand-turned models were converted into casting models.

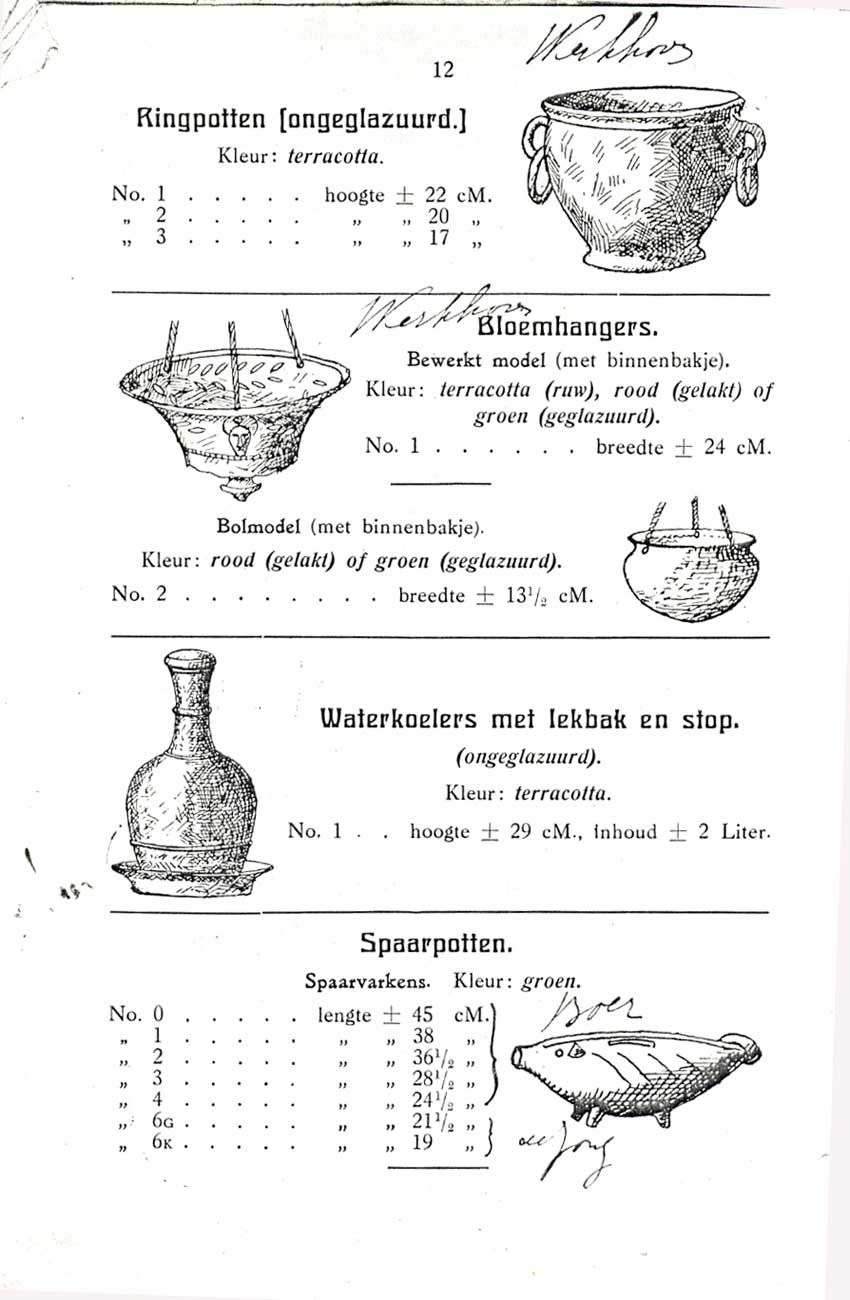

As the oldest branch of the Goedewaagen group, the De Star pottery - the name of the building, incidentally, did not come into being until the 18th century - can be considered the oldest Dutch factory still in existence that produces functional and decorative earthenware. The Ceramics Museum has the glaze recipes of De Star-Goedewaagen from 1921, which led to reconstructions of this Gouda green copper glaze on a piggy bank project of the museum in 2011. On the basis of a preserved printed catalogue from c. 1910 with line drawings of the hundreds of turned models, the museum is working on an exhibition for 2012 on Dutch earthenware for centuries.

The now world-famous potter Willem Coenraad Brouwer learned the craft from the potters of Goedewaagen-De Star from 1898 to 1900. Thanks to a valuable loan from collector Jan H. Branolte, the Ceramic Museum can now document Brouwer's influence on the development of the Arts and Crafts in the Netherlands in his semi-permanent presentation. From 1923 onwards, Goedewaagen offered extensive work experience opportunities to young ceramists who were trained by Bert Nienhuis at the Quellinus school of arts and crafts, later the I.v.K.N.O in Amsterdam. From the 1930s onwards, the production of hand-turned models was transferred to that of cast models.

In the second half of the 1930s, the potters of De Star produced a large series of hand-turned models for a new production line at Goedewaagen, based on designs by the Rotterdam artist Jaap Gidding (1887-1955). Some of these models were later converted into moulds. In 1938-1939 the designer ceramicist Willem Stuurman (1908-1955) also worked for Goedewaagen. A number of hand-turned designs by him are also known. From 1952 to 1959 the potter-designer Zweitse Landsheer (1928-2010) also worked for Goedewaagen. He, too, made an innovative contribution to Goedewaagen's design, particularly for utensils, through hand-turned pottery. A tradition that has lasted for hundreds of years was thus sublimely continued.

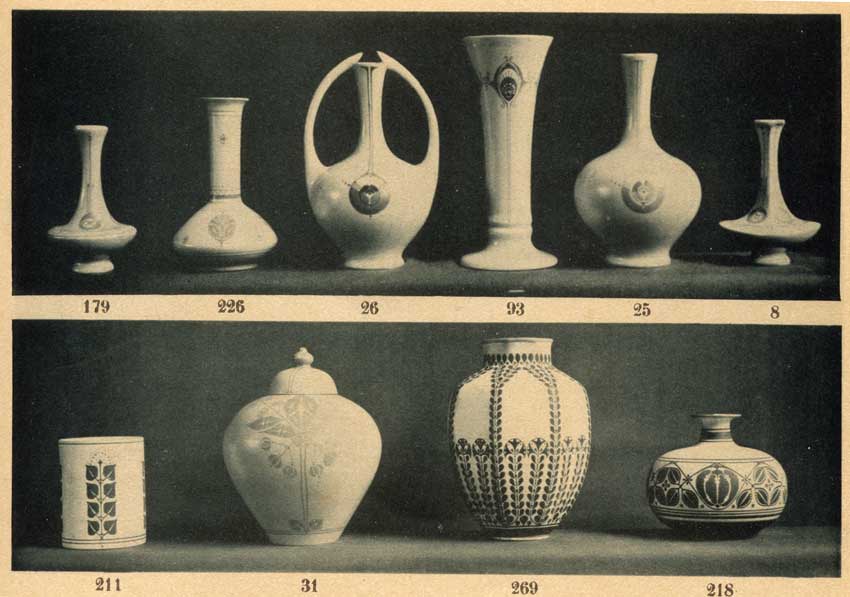

The Plateel- en Tegelbakkerij De Distel (1894) in Amsterdam. Under the management of director Jac. M. Lob, De Distel grew into an art pottery that after 1910 could be considered one of the most important pottery factories in the Netherlands, with work from renowned artists such as Bert Nienhuis, Willem van Norden, Carel Adolph Lion Cachet, Theo Nieuwenhuis, Jan Eisenloeffel and many others.

De Distel was bought by Goedewaagen in 1923 and from that year onwards it was fully integrated into the production of Goedewaagen in Gouda. From 1989 onwards, the Ceramic Museum together with relatives of director Lob and of workmaster Meijer Smeer, participated in the research into the history of De Distel. This research led in 1994 to the first retrospective exhibition of this factory after more than 70 years. The museum was also closely involved in a large exhibition that the Dutch Tile Museum in 2000 dedicated to De Distel.

De Distel's influence on both the production of utilitarian and decorative earthenware by Goedewaagen and that of art pottery by the Goedewaagen-Distel art studio was and is central to various exhibition and research projects of the Ceramic Museum. This resulted, among other things, in a chapter written by the curator about the ceramic oeuvre of Carel Adolph Lion Cachet in a book published by the Drents Museum and Museum Boymans van Beuningen in 1994.

The Kunstaardewerkfabriek Amstelhoek (1897) in Amsterdam. This art pottery factory, initially led by sculptor Lambertus Zijl, achieved its greatest success with the design of Zijl's assistant Chris van der Hoef. Van der Hoef left the Amstelhoek in 1903 to have his designs executed at various factories such as the PZH in Gouda, the Sphinx in Maastricht, the HAGA in Purmerend and the Amphora in oegstgeest. With the help of its lenders, the Ceramics Museum followed Van der Hoef's further development. After the Amstelhoek's bankruptcy, the production of the tile and pottery factory Voorheen Amstelhoek with Van der Hoef's designs was continued by a new owner as Voorheen Amstelhoek. This factory in turn bought the bankrupt estate of the Purmerend factory HAGA in 1907. In 1910 De Distel took over Voorheen Amstelhoek again.

The HAGA Plateelbakkerij (1904). The HAGA factory, originally founded as a sculpture factory in The Hague, took over the business of the Widow Brantjes in Purmerend. In its short existence the HAGA excelled as a sculpture factory that produced designs of the Netherlands' most important sculptors at the time, as a tableware factory after designs by Chris van der Hoef and through decorative and glazing experiments by HAGA director G.J.D. Offermans. When the company went bankrupt in 1907, the mother figurines of some of the HAGA figurines ended up in the collection of the Amsterdam Kunstaardewerkfabriek v/h Amstelhoek. When VH Amstelhoek was sold by De Distel in 1910, these master moulds went to the former competitor. After the purchase of De Distel in 1923 by the Goedewaagen ceramics factory, these HAGA plastiques by Jan Altorf and August Falise, among others, were released by Goedewaagen. Together with its lenders, the Ceramic Museum investigates this history of origin.

In 1965, Goedewaagen acquired all the then current parent shapes from its biggest competitor in Gouda, Plateelbakkerij Zuid-Holland (1898). The PZH, which went bankrupt in 1964, was until then by far the largest manufacturer of decorated earthenware or plateware. After the war, the PZH had become the largest producer of Delft blue decorative earthenware in the Netherlands. Goedewaagen also took over a large number of occasional orders from the PZH, the most notable example being the edition of KLM houses for Bols-Henkes. Partly because the de facto production of the PZH was continued first in Gouda and later in Nieuw Buinen at the Goedewaagen ceramics factory, the Ceramic Museum focused, from its inception, on research into this ceramics factory, most of whose corporate archives had been destroyed in the bankruptcy. The Keramisch Museum was the first museum in the Netherlands to exhibit a large part of the Hageman collection acquired in 1987 by the Stedelijke Musea van Gouda. Two years later, the Gouda museum itself presented a large retrospective of the PZH. Because of the Hageman presentation, in 1994 the Ceramics Museum received the plate collection of Jan H. Branolte on long-term loan, a loan consisting of several hundred PZH pieces. At the moment, several working groups of the Ceramic Museum are conducting further research into various aspects of the factory, see the programme of the Scientific Institute Willem van Norden.

In 1967, Goedewaagen also took over the Plateelbakkerij Quo Vadis (1945) in Gouda and thus acquired a number of good craftsmen who were partly deployed in the second Goedewaagen establishment, established in 1964 in Nieuw Buinen. Gerard van Doorn, a plate painter trained at Plateelbakkerij Zuid-Holland and Porceleyne Fles, was involved in the first inventory of ceramic art objects in the attics of the Goedewaagen factory in 1988. He co-founded the foundation Keramisch Museum Goedewaagen in 1989 and since 2001 has been giving form and content to the workshops organised by the factory and now by the museum.

Gerard van Doorn has also been the house photographer of the factory and museum since 1990. It was also Gerard van Doorn who, when Quo Vadis bought the cabinets with decorative cards from the PZH bankruptcy estate in 1965 and was subsequently ordered to burn duplicates, saved them from destruction. As a result, since 1989 the Ceramic Museum has had on loan more than 300 hand-painted decorative cards.

The restart of the new BV Goedewaagen-Gouda was so successful that in December 1989 the former Gouda Plateelbakkerij Flora (1945) in Hardenberg was taken over. The production of Gouda traditionals and modern design of the Flora was completely integrated into the factory in Nieuw Buinen in 1993. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the Flora gained a prominent role in the Netherlands as a developer of trendy design, the so-called Retro pottery.

In 1991, the Keramisch Museum was the first museum in the Netherlands to make an extensive retrospective of this innovative pottery. In 2006, the museum curator also co-authored a monograph by Stedelijke Musea Den Bosch and Waanders Publishers. Flora Plateel's innovative ceramic design from the 1980s and 1990s, with designs mainly by Floris Meydam, Jeroen Bechtold and Dorothé van Agthoven, was also the focus of a museum exhibition in Nieuw Buinen in 1992.

The Royal Goedewaagen-Gouda BV pottery factory is characterised by the emphatic continuation of centuries-old craft traditions from Gouda, Delft, Amsterdam, Purmerend and The Hague on the one hand, and the most modern technological innovations on the other. Designs from the past are executed again in accordance with the original techniques, such as a watercolour design for a tile tableau from 1903 by De Distel, executed by Gerard van Doorn in 1992. The Ceramic Museum also carried out art-historical research on behalf of the factory, which in turn led to restoration assignments, for example for the replica reconstruction of a seven-part facade tableau of De Distel designed by Bert Nienhuis in 1903 for the shop premises at Herestraat 101 in Groningen. This was followed by a restoration commission for a Distel advertising panel in Wageningen, with guidance from the museum.

In 1996, inspired by the exhibition programme of plateware in the Keramisch Museum, the designers and technicians of the Goedewaagen ceramics factory took up the challenge of producing their own plateware. Auke Beikes designed the opglaze-decor Iris in the style of Gouda mat plateel of the early twenties. The first edition was presented in 1996 in building De Moriaan of the Municipal Museums of Gouda. A year later, the underglaze decor Laila, designed by Beikes, was presented - a decor in the style of the glossy decor Gouda of the PZH from 1905.

On the basis of research by the museum and the new designer Sander Alblas, in 1999 Goedewaagen realised the decor Amata, a playful adaptation of the linear, Purmerend decor by the Vet brothers from 1902 to 1906. This new decor was exhibited in the Purmerends Museum immediately after its presentation. Sander Alblas designed the floral decor Fiore, based on the Haagse Kantjes decor of the eggshell porcelain of Plateelfabriek Rozenburg and its earthenware version of the PZH. For both the Amata and the Fiore editions the museum was closely involved in the choice of relatively difficult plate models to be executed again.

In 1996 and 1997, the museum curator worked as an art consultant for the factory, assisting six Amsterdam artists who, as Dutch Decorators, provided contemporary decors for biscuit models of the former Plateelbakkerij Zuid-Holland. The project was presented in 1997 in the Catharina Guesthouse of the Municipal Museums of Gouda.

With a wink to the hand-turned piggy banks of the Star-Goedewaagen that are exhibited in the Ceramic Museum, designer Robert Bronwasser designed his Money Pig with a gold-glazed snout in 2009. The internationally renowned cartoonist Joost Swarte gave Bronwasser's design a more critical contemporary interpretation.

On behalf of the Royal Goedewaagen Factory, the Ceramic Museum carried out further research into the history of the production of miniatures filled with liquor, when from 1995 onwards a legal conflict flared up between Bols-Henkes on the one hand and Goedewaagen on the other hand concerning the image rights on the KLM houses that were made by Goedewaagen between 1965 and 1995; an order that was transferred by Bols-Henkes to East Asia. The museum's research led to the conclusion that Goedewaagen set up a production line of historical miniatures as a beverage container as early as 1932 and produced two well detailed canal houses in 1939, 13 years before the first KLM house was released to the PZH.

Goedewaagen, tile tableau, after watercolour design by Bert Nienhuis from 1902 for De Distel, Gerard van Doorn design, 1992

Goedewaagen, miniature M2704, corner building Nieuwe Ebbingestraat, Groningen, for contractor Meijering & Benus, 1995

Goedewaagen, piggy bank, design Money Pig by Robert Bronwasser, 2009, decor Joost Swarte, 2010